Decoder #1: Auditions on the End-of-life at Galloping Speed!

DECODER #1: AUDITIONS ON THE END-OF-LIFE AT GALLOPING SPEED!

THE EVENT

From 22nd to 30th April 2024, the 71 members of the special commission tasked with examining the bill on the end of life, auditioned representatives of health workers (doctors, chemists, nurses, nursing auxiliaries), players in the world of old age (old people’s homes, home helps), philosophers, religious representatives and citizens’ associations. In total, 79 people were interviewed for over 35 hours.

THE FIGURE

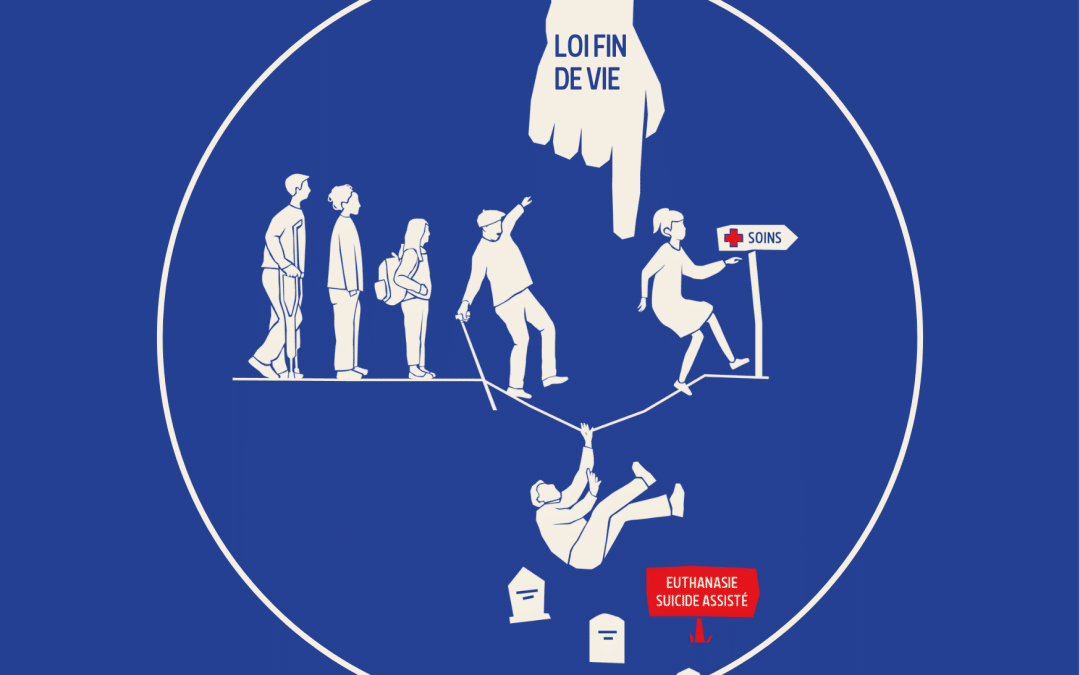

A mere 6 days were assigned for these end-of-life auditions although the bill is intended to introduce a major anthropological breakdown: the lifting of the prohibition on killing.

THE SUMMARY OF THE AUDITIONS

Catherine Vautrin, the Health Minister, opened the series of auditions on Monday 22nd April at 6 p.m. Defending her bill, the minister sought to provide reassurance: “It is not a copy and paste of a foreign legislation, nor a new right or a new freedom, but a possible way ahead to meet situations of suffering which the current law does not address.” She recalled the “strict conditions” for access to assistance in dying. According to her “nobody will force assistance in dying on anyone”.

The very next day, the national councils of the orders of doctors, chemists and nurses were auditioned. Although not expressing direct opposition to the bill, they expressed their doubts concerning its implementation. In particular, Doctor François Arnault, President of the national council of the order of doctors, called for deep thought concerning the “collegiality surrounding the doctor and the patient.” According to him, the doctor “must be able to rely on the support of another health professional when taking his decision.”

The hospital federations, who were auditioned next, highlighted the “concerns of the medical community”, according to Béatrice Noëllec, the representative of the private hospitalisation federation (FHP). In particular, Bertrand Guidet, the President of the Ethics Committee of the French Hospitalisation Federation, asked a question concerning the involvement of health workers of which a certain number refuse to be involved directly. Olivier Guérin, the medical advisor for Fehap (establishments for solidary private home help), tabled the idea of a “collective conscience clause”, covering the entire medical team.

For health workers, freedom of conscience must therefore be guaranteed and safeguards are essential. From the very first day, the criterion of “life expectancy threatened in the medium term” was being questioned, considered as a vague notion. According to François Arnault, “It is not reasonable” for a doctor to have to predict the life expectancy of a patient, “because quite frankly we do not know”.

The round table of the home help players heard a variety of professionals representing retirement homes, a mobile palliative care team, and managers of old people’s homes or home helpers. Without expressing actual opposition to the bill, Pascal Champvert, President of the association of directors for the assistance of the aged gave a warning against ageism: “We are a deeply ageist society which considers that the life of a young person is worth more than the life of the elderly”. The question of access to palliative care for the aged was raised.

Stronger oppositions were expressed on the following day, Wednesday 24th April, when in turn palliative care and religious representatives were auditioned. Doctor Claire Fourcade, President of the French Society for Accompaniment and Palliative Care (SFAP) called for “massive support for palliative care” and “not to legalise euthanasia, even in exceptional circumstances.” Following on from this audition, the religious representatives unanimously expressed their opposition to this bill which “breaks down an essential safeguard, a structuring principle: the prohibition on killing”, as explained by Vincent Jordy, the vice-president of the Conference of French bishops.

At the end of that day, after a more philosophical and sociological audition, a final round table was again convened including various representatives of health professionals. Concerns were again expressed, in particular concerning the aged and vulnerable. Sophie Moulias, the representative of the French Society for Geriatrics and Gerontology (SFGG) warned against ageism. According to her, “the patients whom we accompany are very worried about coming to hospital to be killed because we can no longer treat them.” Professor Pierre-Antoine Perrigault, representing the French society of Anaesthetists and Resuscitators (SFAR), warned about “the danger of prescriptive pressures and the abandoning of the most vulnerable”.

On Thursday 25th April, the round table of associations heard the associations opposed to the bill (Alliance VITA, la Fondation Jérôme Lejeune) and the associations supporting euthanasia and assisted suicide, for whom the text being proposed is still too restrictive (ADMD and Le Choix). The following round table, on the accompaniment of people at their end of life, included the associations of voluntary workers. The President of the association “Jusqu’à la mort accompagner la vie (Accompanying life until death)”, Olivier de Margerie, pointed out the major risk of abuse, in particular for “flagging people”, who risk “to fall” with this bill. “Should one accept a major societal upheaval to solve the case of a relatively small number of people?”.

Also auditioned were the representatives of the Masonic lodge, and on Friday 26th April, representatives of the Economic, Social and Environmental Council (CESE) and the citizens’ convention on the end of life.

The final round table on Tuesday 30th April, involved personalities with commitments on the end of life, either supporting or opposed to the bill. Thus Marie de Hennezel, the author of La mort intime (Intimate death – 1995), Doctor Jean-Marie Gomas, the founder of the French palliative care movement, or Didier Sicard, ex-President of the National Ethics Consultative Committee (CCNE) expressed their firm opposition to the bill. “France, the nation of the protection of human rights should not become the nation where man can be killed”, as warned by Jean-Marie Gomas. On the other hand, Marine Carrère d’Encausse, a doctor and journalist, and Martine Lombard, professor of public law, considered that the bill is too restrictive.

OUR ANALYSIS

Although some concerns were voiced concerning the implementation of the bill, regarding in particular the responsibility of doctors and their conscience clause, few of them really challenged the legalisation of “assistance in dying”, i.e. the possibility of euthanasia or assisted suicide. The principal opposition was unanimously expressed by the players involved in palliative care, the religious representatives and certain associations.

Nevertheless, a criterion was fiercely debated and challenged throughout these special commission auditions, namely “life expectancy threatened in the medium term”. This is impossible to evaluate by doctors, and is considered as an excessively restrictive condition by certain participants, who wish to do away with the notion of “threatened life expectancy”.

Although this series of auditions enabled some 80 participants to express themselves, one can only regret however the very limited time allocated (6 days) for such an important subject, leaving very little time individually for each participant to develop their analysis of the bill.

Finally, absent from these auditions were those most concerned by the bill, namely the sick. No representatives of the handicapped were present, whereas certain people suffering from handicap have publicly expressed their concerns. Also absent, were the representatives of psychiatry who could have provided important information on the understanding of “unbearable psychological suffering”, which constitutes a condition for access to “assistance in dying”.

OUR FAVOURITE CONTRIBUTION

Quite emotionally, Marie de Hennezel, the author of La mort intime (1995), described her experience in palliative care to the members of the special commission:

“Together with the team for which I was the psychologist, we confronted everything which our pro-youth society, which is obsessed with values of efficiency, performance, cost-effectiveness, rejects: the death of others, physical deterioration, extreme vulnerability, the feeling of failure and impotence. Within this dark and murky universe, which is disgusting for some, we discovered a humanity which we did not expect, moments of humanity, tenderness, tactfulness, unexpected gentleness, of which the outside world had no idea. […]

Ceaselessly through my two ministerial reports, my writings, I have been militating for the development of true accompaniment care involving proper training and financial means. You will understand my sadness on learning that accompaniment care is to include suicide assistance and euthanasia, words which I do not even dare to pronounce.”

OUR ALERT CALL

The ex-President of CNSPFV, Véronique Fournier considers that “The very aged suffering from multiple pathologies associated with old age” should have access to “assistance in dying”.