Cost analysis of Medical Assistance in Dying (MAD) in Canada

LEGAL CONTEXT IN CANADA OF MEDICAL ASSISTANCE IN DYING

Medical Assistance in Dying (MAD), i.e. euthanasia, has been available in Canada since 2016 in the context of the so-called Law C-14. Initially, it was available only to those people whose death was reasonably predictable in the short term. 5 years later, in March 2021, Law C-7 modified Law C-14 by extending MAD to those whose death is not reasonably predictable in the short term providing that they are suffering from a serious and incurable disease”. A recent study published by the Cambridge University Press [11] and analysed in a previous expert report, identified the lack of supervision and of control of the justifications for access to MAD resulting in numerous cases of abuse as well as systematic prioritisation of MAD at the detriment of other treatments.

From cost estimates to the estimation of cost savings

In 2020, during the debates concerning bill C-7, the parliamentary budget director’s office [2, 2020] issued a report estimating the financial costs resulting from the bill for the year 2021 “by presenting a breakdown between the costs resulting from the current law (C-14) and the additional costs which would result from the proposed extension of access to MAD (bill C-7)”. This report shows that the establishment of Medical Assistance in Dying in Canada would generate cost savings. It is based in particular on a scientific article published in the Canadian Medical Association’s journal [1, 2017] prior to the establishment of Law C-14. This article transposes the data from nations where euthanasia has been legalised for several decades (Belgium, Netherlands) to Canada in order to demonstrate that the establishment costs could be offset by the cost savings on healthcare expenditure. The range of potential cost savings is very broad, being estimated at between 35 and 137 million dollars per year.

The report [2, 2020] uses the methodology of the article [1, 2017] and adjusts it by extrapolating the statistics recorded since the introduction of MAD in 2016. The cost savings resulting from Law C-14 (taking into account the administrative costs of MAD) were thus estimated at 86.9 million dollars in 2021, by considering that 6465 deaths were attributable to MAD. According to the report, if Law C-7 were to be adopted, 1164 deaths would result from the extension of MAD, representing 62 million dollars of cost savings. In total, the extension of access to MAD would achieve an economy of some 149 million dollars. The tables below show the result of the estimates based on Law C-14 and bill C-7.

Net financial effect in 2021 of the administration of MAD according to the current Law (C-14)

| Number of deaths attributable to MAD | 6 465 |

| Gross reduction in healthcare costs | (Millions of $) |

| Mean cost of end-of-life healthcare | 182.1 |

| Adjustment for palliative care | – 72.8 |

| Total gross reduction in healthcare expenditure | 109.2 |

| Administrative costs of MAD | |

| Doctor’s fees | 8.9 |

| Medicines | 8.6 |

| Supervision organisations | 4.9 |

| Total administrative costs of MAD | 22.3 |

| Net reduction in healthcare costs from the current law (C-14) | 86.9 |

Additional financial effect, in 2021, of the extension of access to MAD proposed through bill C-7.

| Number of additional deaths attributable to MAD | 1 164 |

| Additional financial impact | (Millions of $) |

| Gross reduction in healthcare costs | 66.5 |

| Minus administrative costs incurred for MAD | – 4.4 |

| Sub-total additional net reduction in healthcare expenditure under bill C-7 | 62.0 |

| Total net reduction in healthcare costs (C-14(reference basis) + C-7 (differential) |

149.0 |

| Total net reduction of healthcare costs as a percentage of healthcare budgets | 0.08% |

Under the premise of evaluating the budgetary impact of the bill and ensuring transparency, these reports [1] and [2] dare to quantify the cost savings associated with the establishment of a euthanasia system whilst at the same time claiming not to be seeking to achieve cost savings through such legalisation:

- The authors of [1] thus counter any potential criticism on page 104: “We do not propose Medical Assistance in Dying as a cost reduction measure. At the individual level, neither the patients nor the doctors should consider the costs when making the very personal decision of requesting, or providing the procedure.”

- The authors of [2] specify on page 3: “Many studies have revealed that the healthcare costs during the final year of life (and especially the last month) are out of all proportion: they represent between 10 and 20 % of the total healthcare costs, whereas the people receiving such treatment represent a mere 1 % of population. Nevertheless, the report does not in any way suggest that MAD should be used as a means of reducing healthcare costs”.

How reliable are these estimates?

Article [1] adopts the method from an article published in the United States some 20 years previously [3]. The latter was based on 3 factors in order to evaluate the potential cost savings resulting from the legalisation of medically assisted suicide:

- The proportion of the number of patients requesting euthanasia,

- The effects of the “procedure”, i.e. euthanasia, on the patient’s remaining life expectancy,

- The total costs of end-of-life healthcare.

Estimate of the number of patients “requesting” euthanasia

On the basis of figures recorded in the Netherlands and in Belgium between 1990 and 2012, the article [1, 2017] estimates the percentage of deaths due to euthanasia to be within a range of 1 to 4% of the total number of deaths per year.

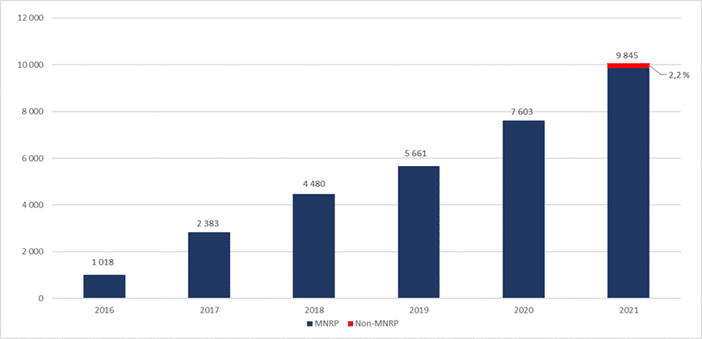

The report [2, 2020] establishes the percentage at 2.2% of the total number of deaths in 2021 i.e. 6465 deaths. This corresponds to an extrapolation of the deaths by MAD in 2019 (i.e. 5661, the latest figures known at the moment of issuing the report). This prediction has been found to be well under the true figure. According to the latest official Canadian statistics, issued in July 2022 [9], 9845 deaths by “MAD-C14” were recorded in 2021 (i.e. 3.3% of deaths). This error of some 30% shows the inability of the public authorities to predict the true impact of these laws.

The statistics also reveal the error in the estimate of the number of additional deaths attributable to MAD in the context of the C-7 extension. In order to calculate this estimate, the report was based on the percentage observed in Belgium of MAD beneficiaries who were not at their end of life. This percentage was 18%. When applied to the prediction of deaths due to MAD-C-14, the estimate for MAD C-7 produces 1164 deaths. In truth, a mere 219 people died in the context of MAD C-7.

Estimation of the “remaining life expectancy”

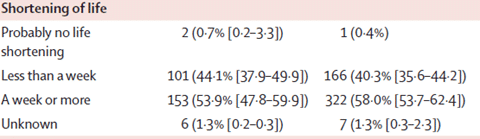

The authors of article [1] make use of a single study [5] conducted in the Netherlands, which indicates that 40 % of people euthanised shortened their life by a week, and

60 %, shortened their life by a month.

Table extracted from reference [5]

This evaluation of the reduction in life expectancy should be treated with great caution: It is based on predictive medical estimates resulting from surveys with no possible means of verification and which are profoundly dependent on the pathology and on the person. Indeed, an article [6] indicates that the diagnosis by doctors on the life expectancy of the patient at the end of life is accurate in a mere 20 % of cases: in 63% of cases the life expectancy is overestimated and in 17% of cases, it is underestimated. The tendency to overestimate has the effect of inflating the cost savings indicated in [1] and [2]. It also has consequences on the delayed date of admission into end-of-life healthcare wards which can result in having to resort to the use of heavy and costly treatments instead of directing patients to palliative care facilities for example in order to improve their quality of life [6]. Whereas it is unreliable, the authors of [1, 2017] consider that this factor has a “considerable impact” on the results of the sensitivity analysis.

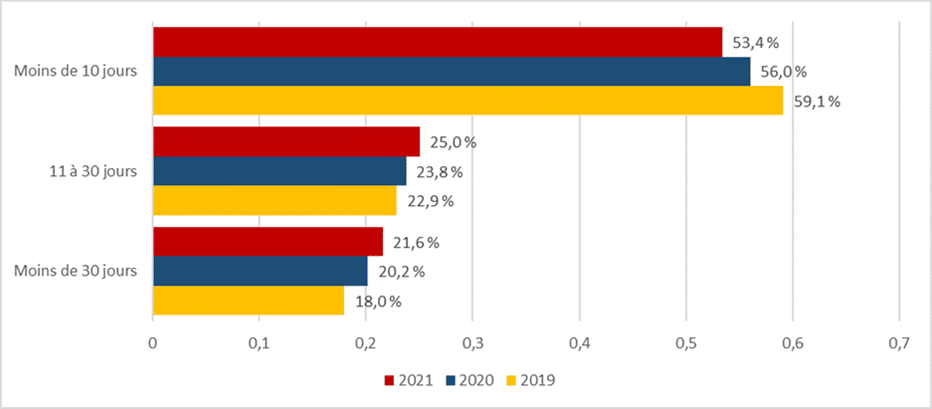

Nevertheless, the report [2, 2020] asserts that in the event of resorting to MAD, “the life expectancy of the patient will be shortened by two weeks in 14 % of cases, a month in 25 % of cases, three months in 45 % of cases, six months in 13 % of cases and a year in 3 % of cases”. Not only do these predictive assumptions fail to include any margin of error, but these figures are moreover at variance with the official statistics, in particular those for 2019. In 2019, 60% of those having registered a request for MAD without obtaining it died within 10 days, 23% between 10 and 30 days, and the remainder (18%) beyond 30 days.

Regarding the remaining life expectancy of the newly eligible patients (C-7) who are not at their end of life, the authors of report [2] evaluate it uniquely for one year with no scientific or statistical basis.

Estimation of the standard costs for end-of-life healthcare

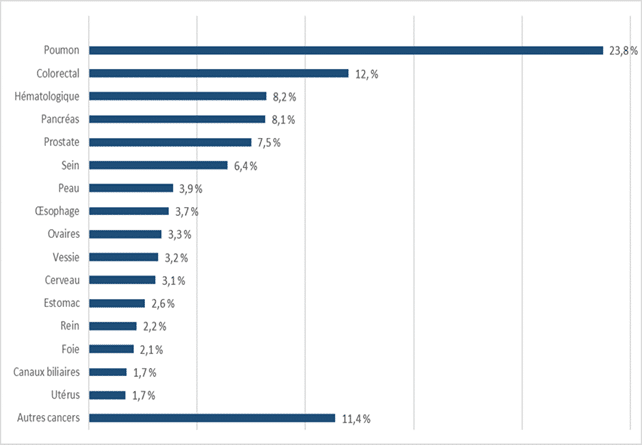

Report [2] shows the healthcare costs of illnesses per age bracket and per sex distinguishing between cancers and other pathologies in Appendix A. However, the cost variations for the treatment of different cancers are not considered although these differ considerably. For example, in [10], the French costs for the 4 principal types of cancers are spread between 14 632€/patient on average for breast cancer, 13 097€ for colorectal cancer, 23 731€ for lung cancer and 7 449€ for prostate cancer.

| No. of patients treated per age bracket | ||||||||

| 0 – 14 | 15-34 | 35-54 | 55-64 | 65-74 | 75 and over | Total | Total cost1 | |

| Breast | 2 700 | 53 600 | 44 200 | 51 500 | 41 000 | 193 000 | 2 824 | |

| Colorectal | 1 200 | 13 100 | 26 700 | 43 100 | 45 700 | 129 800 | 1 700 | |

| Lung | 300 | 9 000 | 22 400 | 28 100 | 19 800 | 79 600 | 1 889 | |

| Prostate | 4 400 | 26 100 | 62 800 | 76 300 | 169 600 | 1 263 | ||

| Other | 5 700 | 26 700 | 97 400 | 121 000 | 181 500 | 238 800 | 671 100 | 8 843 |

| Total | 5 700 | 30 900 | 177 500 | 240 400 | 367 000 | 421 600 | 1 243 100 | 16 519 |

1 Note: Millions of euros, source: Assurance Maladie. Cartography of pathologies and costs.

These variations can be compared with the diseases of patients who requested MAD in 2021:

The approach adopted in [1] and [2] aims to apply a reduction factor associated with the standard end of life costs based on a study [4] which had noted that palliative care could reduce end of life healthcare costs by 40 to 70 % compared with the cost of standard treatments. For simplicity reasons, report [2] applied a reduction factor of 50 % on the standard costs for 80 % of patients who could request MAD. It justifies such an adjustment as follows: “It is reasonable to assume that patients who request MAD could choose a less aggressive approach, such as palliative care.” And thus: “the statistics for Canada in 2019 reveal that 82 % of patients undergoing MAD had been given palliative care during the previous weeks.” A recent article [11] however puts this claim into perspective by underlining that “access to palliative care prior to the availability of MAD was in fact much lower than reported.”

CONCLUSIONS AND DISCUSSIONS

The estimated cost savings resulting from Medical Assistance in Dying procedures in Canada (reports [1, 2017] and [2, 2020]) are based on relatively unreliable assumptions and with no scientific or statistical basis.

When comparing the cost savings with the total costs of the healthcare system in Canada, even if the figure might seem enormous (149 million dollars), it represents a mere 0.08 % of all the health budgets of the provinces for 2021 [2].

In the aging nations, where healthcare costs are weighing down public funds, the legalisation of euthanasia could be interpreted as a temptation for governments to make savings at the expense of the well-being and accompaniment of its citizens.

References

[1] A. Trachtenberg, B. Manns, Cost analysis of medical assistance in dying in Canada, 2017, Canadian Medical Association Journal, Volume 189, Issue 3, https://www.cmaj.ca/content/cmaj/189/3/E101.full.pdf[2] Estimation of the costs of bill C-7 (Aide Médicale à Mourir), 2020 https://www.pbo-dpb.ca/fr/publications/RP-2021-025-M–cost-estimate-bill-c-7-medical-assistance-in-dying–estimation-couts-projet-loi-c-7-aide-medicale-mourir

[3] Emanuel EJ, Battin MP. What are the potential cost savings from legalizing physician-assisted suicide. N Engl J Med 1998;339:167-72, 1998

[4] The Way Forward Integration Initiative. Cost-effectiveness of palliative care: a review of the literature. Ottawa: Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association, 2013. http://hpcintegration.ca/media/24434/TWF-Economics-report-Final.pdf

[5] Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Penning C, et al. Trends in end-of-life practices before and after the enactment of the euthanasia law in the Netherlands from 1990 to 2010: a repeated cross-sectional survey. Lancet 2012;380:908-15. netherlands_euthanasia.pdf (euthanasiadebate.org.nz)

[6] Christakis NA, Lamont EB. Extent and determinants of error in doctors’ prognoses in terminally ill patients: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2000 Feb 19;320(7233):469-72. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7233.469. PMID: 10678857; PMCID: PMC27288. British Medical Journal (nih.gov)

[7] Robert Gramling, Elizabeth Gajary-Coots, Jenica Cimino, Kevin Fiscella, Ronald Epstein, Susan Ladwig, Wendy Anderson, Stewart C. Alexander, Paul K. Han, David Gramling, Sally A. Norton, Palliative Care Clinician Overestimation of Survival in Advanced Cancer: Disparities and Association With End-of-Life Care, Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, Volume 57, Issue 2, 2019,Pages 233-240, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0885392418310571

[8] Gerson SM, Koksvik GH, Richards N, Materstvedt LJ, Clark D. The Relationship of Palliative Care With Assisted Dying Where Assisted Dying is Lawful: A Systematic Scoping Review of the Literature. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020 Jun;59(6):1287-1303 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8311295/

[9] https://www.canada.ca/fr/sante-canada/services/publications/systeme-et-services-sante/rapport-annuel-aide-medicale-mourir-2021.html

[10] https://asteres.fr/site/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/ASTERES-CANCER-FEV-2020-compresse.pdf

[11] Coelho, R., Maher, J., Gaind, K., & Lemmens, T. (2023). The realities of Medical Assistance in Dying in Canada. Palliative & Supportive Care, 1-8. doi:10.1017/S1478951523001025 https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/palliative-and-supportive-care/article/realities-of-medical-assistance-in-dying-in-canada/3105E6A45E04DFA8602D54DF91A2F568