“Palmade scandal”: The impeded mourning for the stillborn child

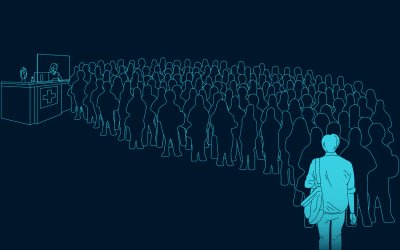

Twenty-one months after causing a serious road traffic accident, whilst under the influence of narcotics, which in particular resulted in a pregnant woman losing her child six months into her pregnancy, Pierre Palmade, the comedian, was sentenced on 20th November 2024 to two years in prison without remission for “accidental injuries” as opposed to “manslaughter”. The sentencing rekindled the debate on the legal status of the foetus.

The Pierre Palmade case underlines the injustice and inhumanity of an artifice in French law which prohibits qualifying as homicide the action of causing the death of a human being before its birth, irrespective of whether the said homicide is accidental or intentional. That artifice led the magistrates to use the term “injuries” to describe the devastation caused to a six-months pregnant woman whose baby lost its life during the accident.

The young woman has since given birth to another child since the accident. Called to the bar to bear witness to her loss to the magistrates, she tearfully described the death of her baby girl, Solin, who was born lifeless:

“He killed my daughter, she was complete, I counted her fingers, she showed me her eyes. She went alone ” (…) “When she was born I was in total denial. For me, I had just given birth. I held Solin in my arms. For me, she was asleep (…) I thought she would be looked after. She was in fact dead.”

The young woman explained that the trauma prevents her even today from cuddling her second baby daughter, conceived after the accident.

Two irreconcilable logics are in conflict:

• First logic: One cannot qualify as homicide a legal abortion, whose legal time limit, according to the 1975 law, extends up to the full term of the pregnancy in the event of likelihood of a particularly serious handicap (precisely when “there exists a strong probability that the child to be is suffering from a particularly serious condition which is recognised as incurable at the time of the diagnosis”). After for a time accepting the qualification of manslaughter for the loss of a foetus, the court of appeals since 2001 refuses any legal recognition of the unborn child.

• Second logic: One cannot deny the pain suffered by parents who lose their child before its birth, nor the harm caused when the death is the result of a mistake, or even a deliberate act. Gradually, the law has indeed attempted to recognise such loss, by reinforcing the signs of the full and total existence of a child who has not breathed.

The 2008 law crossed a first boundary by introducing an “act for the lifeless child” (second paragraph of article 79-1 of the French civil code). In practical terms an officer of the Registry Office issues it on production of a medical certificate, recording the date and place of birth and the names and domicile of the parents.

The law dated 6th December 2021 reinforced such recognition by allowing the appearance in the said act “at the request of the father and mother, of the first name(s) of the child as well as the surname which may be that of the father, or of the mother, or both surnames attached in the order chosen by them, but limited to one surname from each of them.” The act of naming, is a recognition of existence and – hence – of the bereavement.

The concern for humanity which transpires from this provision is asserted by its exceptional retroactive nature, which is extremely rare in law: if the parents so wish, the acts for children born lifeless issued prior to the 2021 law, may in fact be completed with the surname and first names of the child. However, the text specifies, that for all these situations past or future, “such registration of first names and surnames does not incur any legal effect.” Humanity and the law are in conflict.

The debates on the legal status of the foetus are ancient. In antiquity the question was already being asked concerning the inheritance rights of the unborn child, in the event of the death of the father before its birth. And it was life which won over. A famous formula certifies the reasoning elaborated to recognise it, in total justice, in the interests of the child: Infans conceptus pro nato habetur quoties de commodis ejus agitur (A child conceived shall be considered as born whenever that can provide any advantage).

Such a “tradition” should be compared with the possibility provided under French law for “the anticipated recognition of a child”, an optional formality available to unmarried couples, and more particularly to fathers. The establishment of filiation prior to birth enables the father to pass on his surname, to establish his parental authority and to bequeath in the event of death… The unborn child is thus protected.

During the Pierre Palmade case, Maitre Battikh, the lawyer acting for the young mother, had requested re-qualification of “accidental injuries” as “aggravated accidental homicide” Me Céline Lasek, the lawyer defending Pierre Palmade immediately claimed “The foetus never breathed at birth (…), I object!”. When called to the bar, Pierre Palmade, was questioned by the magistrate “Do you accept that such prevention be added to the previous statements?” confirmed such refusal by a single word: “No”. Maître Battikh, whilst not wishing to question the right to abortion, then expressed his regret at the absence of protection for life in utero.

The same lawyer denounced in the media an ” absurd decision”: “Nowadays in France, domestic animals enjoy a legal status; the eggs of certain birds are better protected than the human foetus! It is truly scandalous, it is impossible to carry on with this no man’s land, this legal void”.

Indeed, article L. 415-3 of the environmental code calls for a three-year prison sentence and 150,000 € fine for the destruction of eggs of protected animal species. They may be birds, reptiles, batrachians or even insects. Certainly, it is not – for the moment – the benefit of the animal in question which is here recognised and protected, nor even that of its species. It concerns the benefit to humanity present and future, associated with biodiversity and the preservation of nature. Although striking, the comparison therefore has its limits.

That a human being should be worthy of respect from the very beginning of its existence is the kind of evidence that only a flagrant denial can attempt to smother. But for how long? As the survival of severely premature babies improves, the absurdity of this legal artifice and its inhumanity are becoming all the more obvious.