After more than two months’ work and interviewing 90 end-of-life players, including Alliance VITA, the mission to evaluate the so-called Claeys-Leonetti law dated 2nd February 2016 on the end of life, finally issued its report on 29th March. Although the contributors recognise that the law meets the requirements of the vast majority of end-of-life situations, they identified the inadequacy of the availability of palliative care, a lack of awareness of advance directives and the person of confidence and particularly limited application of deep and continuous sedation until death.

Since January, the evaluation mission interviewed a broad spectrum of end-of-life players, including the authors and reporters of the Claeys-Leonetti law, the French national centre for palliative care and the end of life (CNSPFV), health workers, learned societies, various associations, federations, lawyers, philosophers, authors and religious representatives. The mission chair and reporters also visited a palliative care unit, a hospital and a mobile palliative care team. This was the very first parliamentary evaluation mission of the law, since the evaluations conducted in 2018 by the IGAS (Inspection Générale des Affaires Sociales – General Inspection of Social Affairs) and the Council of State.

The difficulty of evaluating a law in the absence of data

Although the mission was pleased to have achieved a qualitative evaluation of the law, this was far from the case for the quantitative evaluation, due to the current meagre availability of end-of-life data in France. Also, currently, cases of deep and continuous sedation until death are not classified under a specific code and it is therefore not possible to count them with any degree of certainty. There are no data on the routes followed by end-of-life patients. Research conducted on the end of life is also inadequate.

Nevertheless, in spite of the lack of data which hindered the evaluation work, a few major themes emerged from the work performed by the mission.

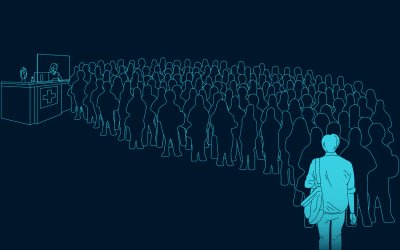

Inadequacy of palliative care

Whereas the Claeys-Leonetti law reaffirmed the right of access to palliative care, the mission recorded the inadequate territorial coverage, with 21 departments which in 2021 still did not yet have a palliative care unit. The mission also observed the shortfall of medical workers, necessarily affecting the palliative care sector.

Advance directives and person of confidence, devices as yet little-known

Based on a survey by CNSPFV dated October 2022 the mission noted that advance directives remain very little-known and that less than 8% of respondents had completed them.

Rare application of deep and continuous sedation until death

The work performed by the mission revealed that the application of deep and continuous sedation until death remains very rare. In the absence of any systematic data, the mission recalled the result of a study which estimated at less than 1% the application of deep and continuous sedation until death within palliative care structures. In practice, the procedure is very difficult to implement outside of a hospital.

The report also showed the uncertainty on the part of carers and family members surrounding this procedure. In the spirit of the law and in accordance with the criteria established by the High Authority for Health (HAS), it is distinguished from euthanasia by the intention, which is not to cause death but to relieve the patient. Nevertheless, the reporters recognised that its implementation may represent a difficulty for carers and for family members in particular when the procedure includes discontinuing hydration and feeding.

The authors of the report also mentioned situations where the sedation lasts longer than intended, where the patient “never ends dying”. The reporters were deeply affected by a sedation on a new-born which dragged on for more than a week.

In such cases, according to their recommendation, it should be permissible for the carers to meet again “in order to decide on the possible adaptation of the care to be provided for the patient”.

This recommendation is troubling, as it involves increasing the doses in order to help the patient to fade away “more quickly”, this would be a deviation towards a logic of euthanasia.

Euthanasia and assisted suicide insidiously in ambush

In conclusion, although the authors deplored the fact that the law is little-known and rarely applied through a lack of means, according to them “the current legal framework instituted by the Claeys-Leonetti law meets the vast majority of situations and, in most cases, people at their end of life do not ask to die if they are adequately cared for and accompanied.”

It is quite surprising therefore, that at the very end of the report, it states that “the current legal framework does not meet the needs of all end-of-life situations, in particular when the patient’s life expectancy is not threatened in the short term.” Without however providing any evidence or data, since that was not the purpose of the mission. Which are the situations being referred to? The reporters go so far as to suggest that the legislator should debate and take up position soon on the question of “active assistance in dying.

This conclusion is troubling, and for several reasons. On the one hand, the report demonstrates that there remains much to be done to better broadcast and apply the Claeys-Leonetti law and that access to palliative care remains seriously inadequate. On the other hand, the report insists on the absence of data and research on the end of life in France. As highlighted by Thibault Bazin, the member of parliament, in his contribution to the reports, any change in the law governing these conditions could result in “active assistance in dying” being requested by default, in the absence of being able to provide a satisfactory accompaniment for the end of life.

This report shows that the urgency is not so much to legislate again but rather to develop adequate means for the accompaniment of patients at the end of their life.