Demography in China, what is the reality of birth rate support?

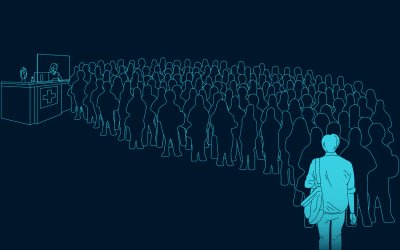

The support for birth rate, including for a third child, announced in 2021 by the Chinese Politburo, has not yet produced any real effect on demography.

The National Statistics Bureau has announced a drop in the population, the first in 60 years. At that time, a devastating famine, which started in 1959, had caused some 36 million deaths, according to a book by Yang Jisheng, the historical journalist.

The current drop announced is of 850,000 inhabitants. Projections indicate that India is set to become the most populated nation in the world from this year.

The UN, in its projections for 2019 predicted a peak in birth rate for China around 2031. However, the rate of fertility has continued to fall and has established at 1.15 in 2021. The scenario of a demographic winter for China seems to be confirmed. The economic and social impacts are expected to be far-reaching: equilibrium between the active and retired populations, pressure on the care for the aged, decrease in economic productivity, weight of China in the geopolitical arena etc.

Certain media describe this drop as “paradoxical”. The relaxing followed by the official ending of the brutal single child policy dates back several years. However, the factors listed to explain the low level of fertility are jointly cultural, social and economic, and cannot be countered by mere incitation by the public authorities. Rise in the cost of living, inadequate housing, habit of small families, pregnancies deferred to a later date, more women taking higher education, but also a reduction in the desire to raise children according to surveys of young Chinese. He Yafu, a Chinese demographer, noted in an article in Le Monde “The reduction in the number of women of childbearing age, has reduced by 5 million per year between 2016 and 2021“. The aging of the population is a self-sustaining phenomenon.

Birth rate in France

In France, where the current debate on the pensions system has a demographic aspect, the Budget Minister recently stated in the press that “birth rate support is not at all a taboo subject for the government.”

But more than a birth rate policy, the stake is a culture where the welcoming of a child, from the very outset of pregnancy, is sustained and valued. This is a challenge in many nations, quite apart from the Chinese case.

The policy of the single child in China and its consequences

The policy of the single child, introduced by Deng Xiaoping in 1980, was relaxed in 2013, with no resulting increase in the rate of births: of the 11 million couples potentially concerned by this reform, a mere 620,000 asked for such authorisation. In 2015, the plenum of the Central Committee announced that all couples would be authorised to have two children from 1st January 2016. The Chinese approach therefore remained particularly administrative and coercive. The Chinese Health Minister established a report on the results of tens of years of control, estimating the number of abortions at 281 million between 1980 and 2010. A forced sterilisation policy had also been implemented.

The impact of this demographic policy has had deep repercussions. The official announcement underlines the economic angle. In 2010, two active adults shared the burden of one economically dependent person (child or pensioner). Current projections show that in 2050, China will have some 250 million active workers less and each active worker will have to bear the burden of nearly one economically dependent person. A book published in 2017 by Isabelle Attane, a research worker at INED (French National Institute for Demographic Studies), already identified the risk in China of “becoming old before becoming rich.”

But the birth limitation policy also had many social effects, such as the imbalance of the Man/Woman ratio with 107 men for 100 women in 2015, whilst in France there are 92. This imbalance has detrimental effects in itself, such as the trafficking of women.

The first reactions in the media and the social networks seemed to indicate that this new voluntarist directive by the Chinese authorities would not necessarily achieve results. Many factors are listed: the absence of support for mothers, the cost of housing and education, the difficulty in trying to reconcile family and professional obligations for women, the reduction in marriages, the mentality inculcated by decades of birth limitation policies etc. An article in the New York Times mentioned the results of an on-line poll by the Xinhua agency on the question “Are you ready for the 3-child policy?”. Of the 22,000 replies, 20,000 chose the answer “I do not envisage it”. It does not appear that a new “baby boom” is likely in that context.

It is particularly astonishing to note the virtual absence of any international criticism of the coercive and highly liberticidal Chinese policy. The Chinese State has intervened excessively for decades in the private and intimate lives of the Chinese people, with no reaction by the international organisations responsible for human rights.