After extending access to euthanasia for people whose natural death is not “reasonably predictable” a mere 5 years after passing the first law in 2016, Canada intends to organise its access for people suffering from mental disease as of 17th March 2023.

Euthanasia, designated by the expression “Medical Assistance in Dying” (MAiD) in Canadian law, was made available in 2021 to any person suffering from a serious and incurable condition and who wishes to die. Since then, the media have reported troubling cases of euthanasia whereas handicapped or sick patients wished to continue to live. In particular people in situations of poverty or who are deprived of adequate health care make such requests, because they have no other options as described in a recent article.

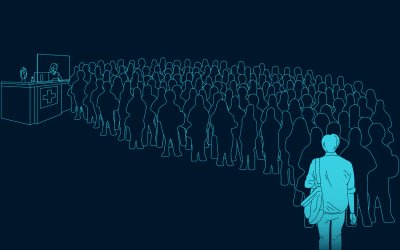

This escalation in euthanasia requests is striking. As a comparison, in California, a State demographically comparable to Canada (40 million inhabitants) and which also legalised assisted suicide in 2016, 486 people died by assisted suicide in 2021 whereas in the same year, 10,064 people died by “MAiD” in Canada, i.e. some 3.3% of all deaths.

Controversy over the evolution on the law on euthanasia in Quebec

Quebec has not yet transposed the evolution of the Canadian federal law: a bill is due to be tabled shortly. An initial bill (C-38) which was tabled in May 2022 was the subject of considerable controversy. Apart from transposing the federal law, it is also intended to authorise an anticipated request to die “for people suffering from serious and incurable conditions leading to inaptitude”. This concerns in particular, those suffering from Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, and Parkinson’s in certain cases. Several associations reacted against the absence of discussion on the matter.

Euthanasia and mental disease

At the federal level, the 2021 law had excluded mental disease until 17th March 2023 in order to allow time for the government to evaluate the conditions for proposing euthanasia or assisted suicide with adequate safeguards. The law called for the Justice and Health Ministers to meet a group of experts “tasked with examining the protocols, the orientations and safety measures relative to MAiD in the case of people suffering from mental disorders”. This working group put forward regulatory recommendations in a report issued in the spring of 2022.

According to the experts, “Although there is a strong link between death by suicide and the existence of a diagnosed mental disorder, the vast majority of people suffering from mental disorders do not commit suicide (…). In any situation where suicidal tendencies are a concern, the doctors must consider three complementary perspectives: consider the ability of the person to provide enlightened consent or to refuse treatments, determine whether interventions to prevent suicide – including involuntary interventions – should be triggered, and propose other types of interventions which could help the person.”

These distinctions could be difficult to evaluate. And as noted by a reporter analysing the impact of the law and its extensions on the prevention of suicide “Who benefits from the prevention of suicide and who benefits from the facilitation of suicide? If death is executed on the basis of the momentary consent of a person, then where is the legitimacy of attempting to dissuade a person in distress?”

The extensions to the conditions for applying euthanasia observed in Canada show how the promises of strict control of this practice have proved to be untenable. This is a crucial reality to be considered in the debate which is opening in France on a possible evolution in the law.