A recent editorial in the journal Nature has highlighted the alarming rise of complex genetic testing for selecting human embryos in vitro.

The emergence of companies offering prospective parents tests based on a “polygenic risk embryo score” prior to in vitro fertilization (IVF) has alarmed geneticists and bioethicists. Moreover, the European Society of Human Genetics, the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology and the American College of Medical Genetics have all advised against using these tests in clinical practice.

Simple genetic tests are already used in France for Preimplantation Genetic Diagnosis (PGD) to screen for rare and serious diseases related to single gene mutations. In the UK, these tests have been approved for more than 600 inherited disorders.

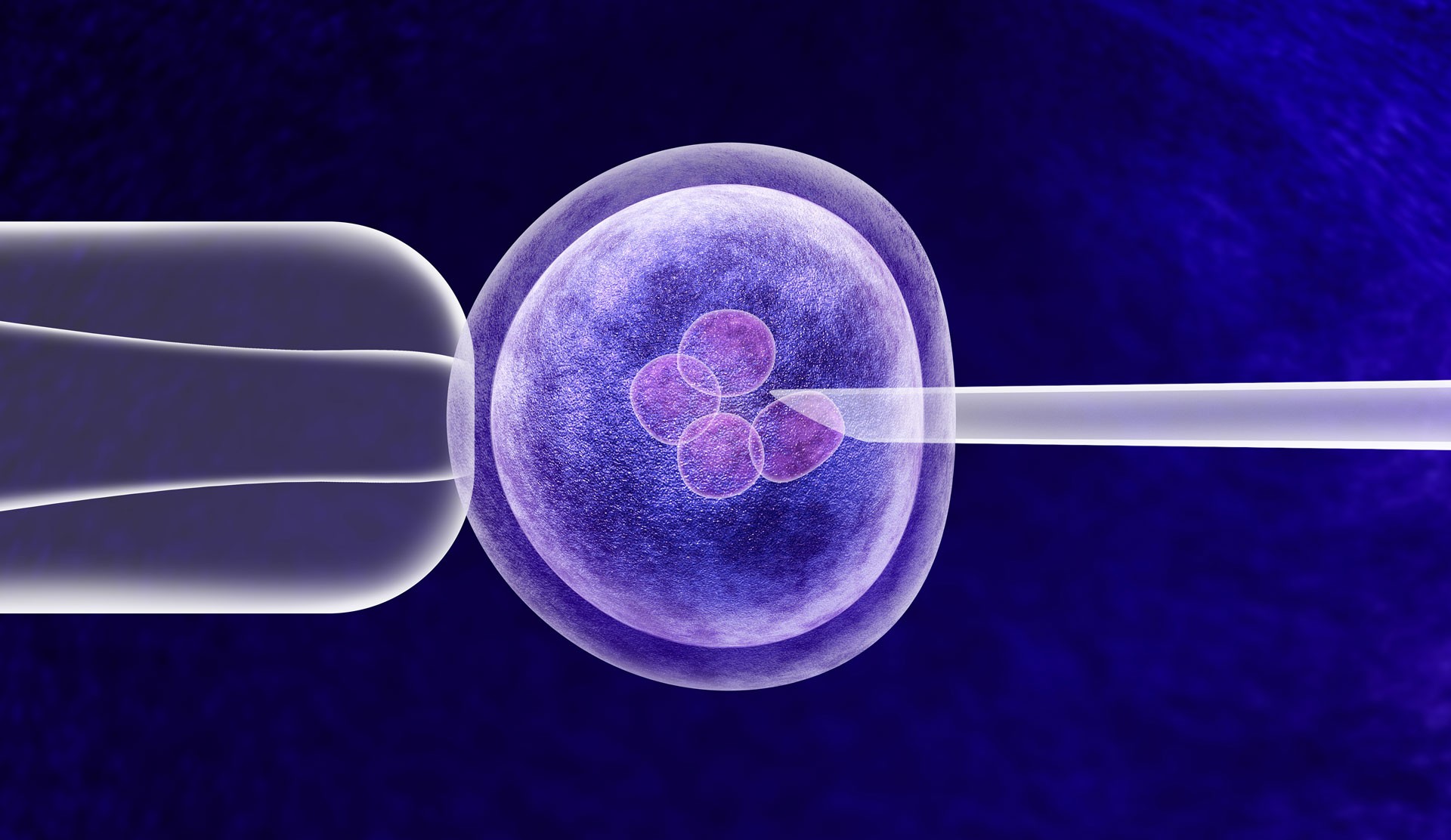

Now, companies such as Myome in California, claim that almost all the DNA of a days-old embryo can be deciphered or “reconstructed”, making it possible to predict the risk for many common diseases, even those that develop decades later, or those influenced by dozens or even hundreds of genes. With current technologies, it is very difficult to accurately sequence a whole genome because of the tiny volume of genetic material available in a few cells biopsied from an embryo for analysis. To be able to make these predictions the company uses another method, described in an article: sequencing the DNA of both parents, and “re-building » the embryo genome using these data. Thus they sequenced the genomes of 10 couples who had babies through IVF. They used the data collected from the couples’ embryos, 110 in all, which had already undergone simple genetic testing to check the number of chromosomes and look for some well-identified genetic abnormalities.

By combining these embryo data with the more complete parental genome sequences, and applying statistical and population genomic techniques, the researchers believe they are taking into account the genetic shuffling that occur during reproduction. They have compared their theoretical results with the genome of the few children born among these couples and they consider the results to be encouraging.

Nonetheless, the reliability of these predictions is completely dubious, and the societal risks and implications are not sufficiently addressed and explained.

The risk scores have been developed on the basis of predictions which may prove to be incorrect. One problem is that the scores currently available are not based on an appropriately diverse subset of people since the database is composed of DNA studies from populations of overwhelmingly European ancestry. They would be less precise with other groups of population. Moreover, creating an embryo risk score based on adult DNA is not an easy task, given the complexity of genetics and because environment has a high impact in disease occurrence.

According to Shai Carmi, a statistical geneticist at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and his coworkers: “It is difficult to say if this will make sense”.

In their research, computer modeling was used to assess whether height and IQ can be boosted by selecting embryos using polygenic risk scores for either trait, and found that generally, it doesn’t work.

The results are sometimes predictable only due to gene interactions which are still not well understood between the multiple genetic and environmental factors accounting for diseases. Second, scientists do not yet fully understand why some embryos, selected because of a lower risk for one disease, are actually more vulnerable to other infections. Norbert Gleicher, an infertility specialist at the Center for Human Reproduction in New York, worries about the unintended consequences of applying polygenic risk scores to embryos, and calls this practice unethical, “You can achieve omission of one disease but at the same time, doing this, induce another disease.” It is known that a DNA sequence associated with one beneficial characteristic can also increase the risk of a detrimental one, and that some genes identified as predisposing to a certain pathology protect against others.

Finally, these polygenic risk scores are being used to predict the risk of disorders that occur later in life. However, there is no way of knowing what treatments or preventive steps will be available by the time these embryos reach adulthood.

Despite these serious uncertainties, these polygenic risk assessments are already being marketed to consumers in some countries, in the United States and Japan for instance, without clearly informing the individuals on these techniques’ uncertainties and risks. The authors of the Nature editorial declared “…the scores of such assessments could be harmful. They could trigger the unnecessary destruction of viable embryos or induce women to undergo extra cycles of ovarian stimulation to collect more oocytes.”

The world market of preimplantation genetic testing (PGT), associated with that of artificial procreation and IVF is booming. It was already estimated at $75 million in 2018.