Lou Gehrig’s disease, or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), is also known as Charcot’s disease. This serious and still incurable pathology is a neurodegenerative disease that results in progressive paralysis of the muscles involved in voluntary motor skills. It also affects the ability to make sounds and to swallow. This is due to the gradual loss of motor neurons, the nerve cells that direct and control voluntary muscles. Both types of motor-effecting neurons are involved: the central ones, located in the brain, and the peripheral ones in the brain stem and spinal cord. Patients usually only survive 3 to 5 years after diagnosis. Although no cure is currently available, the medium-term prospects are encouraging due to recent research which has improved genetic and biological knowledge of this disease.

A 34-year-old German patient was diagnosed in August 2015 with a fast-progressing form of ALS. By the end of 2015, he’d lost the ability to talk and walk. The next year he was placed on a ventilator because he couldn’t move his muscles to draw breath. In the beginning, he could communicate using an eye-tracking device and assistive technologies, which used his eye movements to assemble words and sentences. But by August of 2017, the German man couldn’t even do that, because he’d lost the ability to fix his gaze.

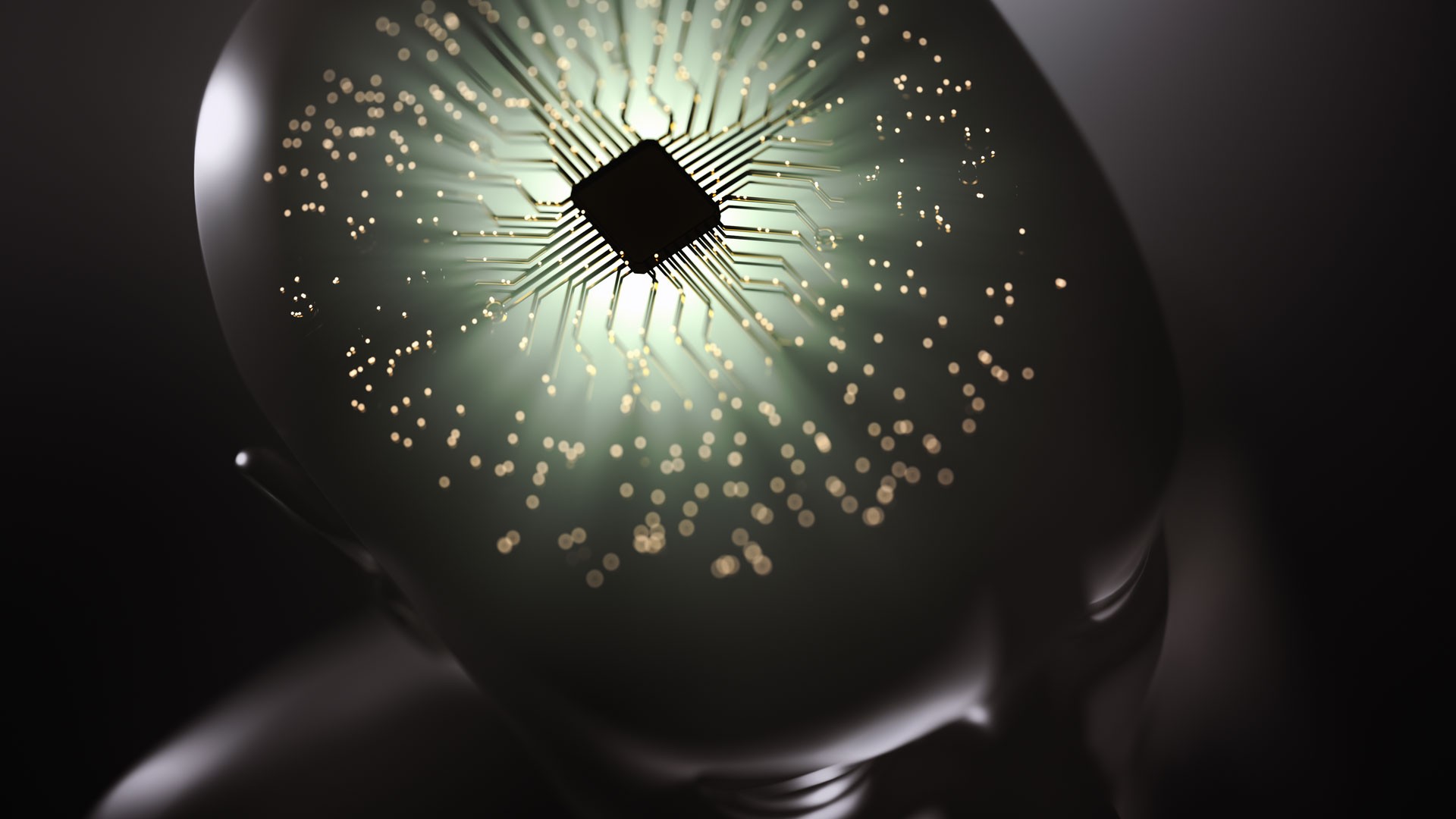

But with a new brain implant placed inside his motor cortex (the part of the brain responsible for movement) he has regained his ability to communicate with family and doctors. Two microchip implants, each with 64 needle-like electrodes that detect neural signals allow him to form words and even full sentences, by using nothing but mental impulses. The implants pick up his brain activity and feed it into a computer as a “yes/no” signal. A spelling program reads the letters of the alphabet aloud, and the man selects specific letters using his brain waves. The process is slow – about one letter per minute, but it has allowed him to regain some communication with those around him. “It shows that you can write sentences with the brain even if you are completely paralyzed without any eye movement or other muscles to communicate,” said lead researcher Niels Birbaumer, director of the Institute of Medical Psychology and Behavioral Neurobiology at the University of Tubingen, in Germany.

Unfortunately, the technology involved in this brain-computer interface is still complex and very expensive, and requires much time and dedication, said co-researcher Jonas Zimmermann, a senior neuroscientist with the Wyss Center for Bio and Neuroengineering in Geneva, Switzerland. For the person to effectively communicate, caregivers must be trained to set up the system and validate the patient’s responses, he explained. “At the Wyss Center, we are developing a fully implantable device which will reduce the risk of infection and be easier to set up and control. The system is currently in pre-clinical verification. We plan clinical trials in the near future.” That wireless device, named ABILITY, “could enable speech decoding directly from the brain as the patient imagines speaking, leading to more natural communication.”

This research aimed at improving patients’ relational skills and therefore their quality of life, is a beneficial service for human progress. Supporting technological innovations to guarantee the protection of the most vulnerable is one of Alliance VITA’s 3 main priorities to put humanity back at the heart of all public policies. Please refer to our recommendations for the presidential platform.

For more information: Evaluating How to Best Manage Charcot’s disease (ALS)?