In France, a Parliamentary investigational committee was appointed to evaluate the management and the consequences of the coronavirus crisis. After 6 weeks of hearings, on July 28, the rapporteur Eric Ciotti, (MP for the Alps Maritime region) presented the committee’s preliminary findings on the elderly.

What are the preliminary findings?

France was ill-prepared and failed to anticipate this major crisis, as shown by the trend of masks supply over the past ten years. A new policy had been issued in 2013 by the General Secretariat for Defense and National Security (“SGDSN”) which rendered all employers responsible for managing their own stockpile of masks. This policy change included healthcare establishments. Nevertheless, those responsible for public and private hospitals and nursing homes were not informed. In 2009 a total of 2.9 billion masks were available, but the stockpile had dwindled to 100 million by the time the crisis began.

In 2018, when informed that practically all the masks were expired, the Directorate General of Health (“DSG”) only ordered 50 million new masks, barely 0.05 % of the estimated 1 billion masks recommended in the event of a flu epidemic.

As of January 2020, scientists and the French government did not seem to have fully assessed the potential extent of the coronavirus crisis. Only by March an action plan was elaborated but it was too late. Insufficient testing was a major factor which contributed to the spread of the epidemic during the initial stages of the crisis. By mid-March, France had only tested 12,000 people, compared to Germany where 500,000 citizens had already been tested. According to the rapporteur, the belated response time was partly due to unnecessary competition between laboratories and to administrative roadblocks. In addition the crisis was exacerbated by the slow-moving French bureaucratic system.

Was there triage of patients?

In hospitals almost all non-Covid patient care was postponed, the side effects of this delay having not been evaluated yet.

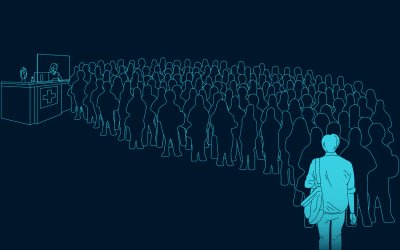

Doubts are raised by the fact that statistics point to a significant decrease in the number of elderly treated in intensive care units (ICU). The French newspaper “Le Monde” quotes the rapporteur as saying: “At the beginning of April at the summit of the crisis, the number of people over 75 years admitted to intensive care fell substantially. The average number of elderly in ICU dropped from an average of 25% (based on previous years for the same period) to 14% during the crisis, and as low as 6% in the metropolitan Paris region (Ile-de-France). Our healthcare system was overwhelmed, which consequently reduced the chances for caring for the elderly. Many could possibly have been saved. This is very alarming. ”

Numerous doctors who coordinate care in medicalized nursing homes deplored the lack of protective equipment (masks, gowns, etc) when the crisis began. Centralized hospital care, a hallmark of the French health system, took its tolls on the population. In the beginning only the hospitals performed coronavirus testing, while private laboratories were excluded. Likewise, the public emergency services (“SAMU”) were stretched beyond capacity, while 60,000 doctors in private practice were barely called upon.

The preliminary findings by Parliament’s investigation committee concur with Alliance VITA’s press release issued as soon as March 26, 2020 which warned that the epidemic put the elderly at a greater risk of discrimination and euthanasia. “Alliance VITA requests for the public authorities to include the elderly in the COVID-19 death statistics, to screen all citizens regardless of age, and to reconfirm that individuals of all ages have a right to healthcare treatment without being killed.”

According to the committee’s preliminary findings, France now appears better prepared to handle a potential second wave of coronavirus. Nonetheless, the committee recommended implementing several structural changes: private health care providers need to be more closely included in crisis management, healthcare reservists need to be called to a greater extent, and resuscitation services need to be continuously improved and sustainable.

It is imperatively urgent to better take into account the elderly who suffered the most during the epidemic; to provide improved medical services in nursing homes, and to encourage and recognize the value of in-home care and support services.